[vc_row el_class=”intro”][vc_column width=”1/2″ el_class=”intro-content”][vc_column_text][page_breadcrumbs][/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”Our Treatment Approaches” font_container=”tag:h1|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_custom_heading text=”” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text][/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content_no_spaces” css_animation=”bounceInUp”][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”What is Evidence-Based Practice (EBP)?” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text] The most common definition of Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) is from Dr. David Sackett. EBP is “the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of the individual patient. It means integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research.” (Sackett D, 1996)

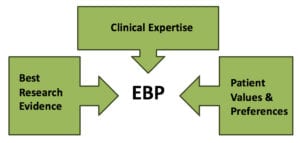

The most common definition of Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) is from Dr. David Sackett. EBP is “the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of the individual patient. It means integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research.” (Sackett D, 1996)

EBP is the integration of clinical expertise, patient values, and the best research evidence into the decision making process for patient care. Clinical expertise refers to the clinician’s cumulated experience, education and clinical skills. The patient brings to the encounter his or her own personal preferences and unique concerns, expectations, and values. The best research evidence is usually found in clinical relevant research that has been conducted using sound methodology. (Sackett D, 2002)[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Assertive Community Treatment” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]Multi-disciplinary continuous treatment teams provide individualized services, skills training and support in community settings for people with serious mental illness. Clinical trials have shown reductions in hospital use and symptoms, and improved satisfaction with services. National performance monitoring data have confirmed these effects as well as improvements in alliance, functioning and quality of life with maintenance of program fidelity over seven years. Successful teams have served as mentor-monitors for new programs.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Cross-Cultural and Ethnic Issues” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]SAMHSA National Standards for Cultural Competence

The Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education (WICHE) has been known for its work in cultural competence across the last 2 decades, long before the concept was popularized. WICHE with Marie Sanchez (now Executive Director of the Latino Behavioral Health held many conferences and meetings with panels from across the country which created the SAMHSA National Standards on Cultural Competence (USDHHS, 2000). The 72 members of these panels represented academics, clinician, administrators, family members, and consumers from across the nation and the 4 underrepresented groups: Native American, African, Latino, Asian and Pacific Islanders descent. The panels met at Georgetown University and created a core set of competencies for agencies serving the mentally ill. There are benchmarks, outcome measures, and standards. These are the only national standards of any kind approved by SAMHSA.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Cognitive Rehabilitation” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]Thinking Skills for Work Program

In the cognitive rehabilitation programs section of therapeutic Interventions, the Thinking Skills for Work Program should be added:

The Thinking Skills for Work Program is a cognitive remediation program designed to improve employment outcome in persons with severe mental illness. The program is provided in the context of supported employment and includes four components: a) cognitive and work history assessment; b) 24 sessions of computer cognitive training exercises over approximately 4 months using Cogpack 6.0 (Marker software), a commercially available software program, facilitated the cognitive specialist; c) collaborative job search planning with the client, employment specialist, and cognitive specialist.; and d) job support consultation in which the cognitive specialist provides consultation to the employment specialist and client to address any work-related programs or unmet needs. Collaborative job search planning takes place at any point during the program, depending on the client’s preference. Variations of the Thinking Skills for Work Program have been implemented in other vocational rehabilitation programs.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Cognitive Behavior Therapy” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Psychosis (CBT)

The premise of CBT is the cognition, the process of acquiring knowledge and forming beliefs, can influence mood and behavior. CBT techniques help patients to identify and correct thoughts and misinterpretations of experiences that are at the root of aberrant behavior. Schizophrenia patients typically have information processing biases and deficits in abstract reasoning and cognitive flexibility that may contribute to maintenance of delusional beliefs. CBT modifies these cognitive processes and challenges beliefs underlying delusions, hallucinations and negative symptoms. Patients are introduced to the general concepts of CBT, including the relationship between thoughts, actions, and feelings (generic cognitive model), automatic thoughts, thought challenging by examining evidence for beliefs, and mistakes in thinking (e.g., jumping to conclusions; mind reading; all-or-none thinking). Patients are taught to identify thoughts, identify relationships between thoughts, feelings and behaviors, and identify mistakes in thinking. Behavioral experiments are conducted inside and outside of sessions (homework), in order to gather evidence to evaluate beliefs. Alternatives therapy, Socratic questioning, thought chaining, and thought records are used to help patients examine the logic of beliefs underlying positive and negative symptoms and generate more adaptive alternative to mistakes in thinking or thoughts without sufficient evidence.[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT)

DBT was originally developed as a broad array of cognitive and behavior therapy strategies addressed to the problems of Borderline Personality Disorder, including suicidal behaviors. More recently, it has been increasingly used for people with Schizophrenia.

Stylistically, DBT blends a matter-of-fact, somewhat irreverent, and at times outrageous attitude about current and previous parasuicidal and other dysfunctional behaviors with therapist warmth, flexibility, responsiveness to the patient, and strategic self-disclosure. Emotion regulation, interpersonal effectiveness, distress tolerance, core mindfulness, and self-management skills are actively taught. In all modes of treatment, the application of these skills is encouraged and coached. Throughout treatment, the emphasis is on building and maintaining a positive, interpersonal, collaborative relationship between patient and therapist. A major characteristic of the therapeutic relationship is that the primary role of the therapist is as consultant to the patient, not as consultant to other individuals.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Trauma Informed Treatment ” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for PTSD in SMI

The CBT for PTSD in SMI program is a 12-16 week individual program focusing on the treatment of PTSD in persons with severe mental illness. The program is primarily based on cognitive restructuring and does not include therapist directed exposure therapy. The program includes the following components: a) Orientation to Program; b) Developing a Crisis Plan; c) Breathing Retraining; d) Education about PTSD; e) Education about Associated Symptoms and Problems; f) Cognitive Restructuring I: Common Styles of Thinking; g) Cognitive Restructuring II: The 5 Steps of Cognitive Restructuring; h) Generalization Training; and i) Termination.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT)” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]CPT is a 12 session therapy that has been found effective for PTSD and other corollary symptoms following traumatic events. CPT is based on a social cognitive theory of PTSD that focuses on how the traumatic event is construed and coped with by a person who is trying to regain a sense of mastery and control in his or her life. The other major theory explaining PTSD is Lang’s (1977) information processing theory, which was extended to PTSD by Foa, Stekette, and Rothbaum (1989) in their emotional processing theory of PTSD. In this theory, PTSD is believed to emerge due to the development of a fear network in memory that elicits its escape and avoidance behavior. Mental fear structure include stimuli, responses, and meaning elements. Anything associated with the trauma may elicit the fear structure or schema and subsequent avoidance behavior. The fear network in people with PTSD is thought to be stable and broadly generalized so that is easily accessed.

When the fear network is activated by reminders of the trauma, the information in the network enters consciousness (intrusive symptoms). Attempts to avoid this activation result in the avoidance symptoms of PTSD. According to emotional processing theory, repetitive exposure to the traumatic memory in a safe environment will result in habituation of the fear and subsequent change in the fear structure. As emotion decreases, patients with PTSD will begin to modify their meaning elements spontaneously and will change their self-statements and reduce their generalization. Repeated exposures to the traumatic memory are thought to result in habituation or a change in the information about the event, and subsequently, the fear structure.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT)” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]Behavioral Family Therapy (BFT)

BFT is a single family psychoeducation model designed by developing collaborative working relationships between a client’s treatment team and his or her family, including the client, in order to better manage the psychiatric disorder, reduce stress in the family, help the client make progress towards personal recovery goals, and improve the well-being of everyone in the family. The program includes the following components: a) assessment of each family member and the family as a whole; b) psychoeducation about the nature of the psychiatric disorder and the principles of its treatment; c) communication skills training; d) problem solving training; and e) special problems. The family program is usually provided over a 9 to 24 month period.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Substance Abuse and SMI” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]Integrated Dual Disorders Treatment (IDDT)

This model specifies that the concurrent treatment should be provided for severe mental illness and substance use disorder (dual disorders) by the same clinical or team of clinician, with the treatment team assuming responsibility for integrating the treatment of the two disorders. Integration treatment emphasizes; the use of assertive outreach to engage clients in treatment and provide as needed assistance in the community; motivational enhancements to address one’s substance use problems and better manage one’s mental illness; reduction of harmful consequences relative to substance use; cognitive-behavioral therapy strategies to help people develop skills for refusing offers to use substances, prevent substance abuse or mental illness relapses, and cope with symptoms or cravings; collaboration with significant others; comprehensiveness to address the broad range of social, health, housing, and medical needs; and long-term treatment when needed. Multiple treatment modalities are employed, including individual, group, and family approaches.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Supported Employment” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]Placement of clients in competitive jobs with using the place and train approach, with provision of support to address obstacles to successful performance. The defining features of the IPS model are all incorporated into SAMHSA’s toolkit on supported employment (downloadable at www.samhsa.gov ), including the fidelity scale.

Integrated SE and ACT Program

ACT subteam operates according to PACT model standards but does not provide vocational services. The SE subteam adheres to its program model standards. Both subteams work side-by-side as a self-continued program at all times. ACT-IPS aims at reducing interference of illness symptoms while vigorously backing efforts to promote client’s efforts to succeed in the competitive labor market. Employment Specialists coordinate multiple vocational service cycles of assessment, planning, counseling, and job development/finding, while enlisting ACT staff to help clients control illness symptoms and break through cognitive, emotional, and behavioral impairments to perform well on the job, cope with and learn from job endings, and undertake new job searches.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Illness Management and Recovery” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]Illness Management and Recovery

“Illness Management and Recovery (IMR) consists of a series of weekly sessions in which specially trained mental health practitioners help people who have experienced psychiatric symptoms develop personal strategies for coping with mental illness and moving forward in their lives. The program can be provided in an individual or group format, and generally lasts between 3 to 6 months.” (IMR Implementation Resource Kit)

Eleven modules (which include educational handouts for participants) cover such subjects as recovery strategies, practical facts about mental illness, the Stress-Vulnerability Model of mental illness, building social supports, reducing relapses, using medications effectively, coping with stress, coping with problems and symptoms, substance use, healthy lifestyle habits, and getting needs met in the MH system.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]